Whence metroidvania

Tuesday, April 15, 2025

Comments: (live)

Tagged: metroidbrainia, genre, craft, design, puzzles, if, interactive fiction, infocom, adventures, outer wilds, zork, myst, the prisoner, hadean lands, graham nelson

A few days ago, Kate Willaert wrote:

As much as I love the word "Metroidvania," I dislike people calling these games Metroidbrainias because it makes it sound like their root is in Metroid games when they're just standard Adventure games in real-time. But Adventure is now obscure compared to Metroid, so we have to say it's that? [...] Although I completely admit I might be misunderstanding some essential component of what classifies a thing as a MetroidBrainia. Perhaps the first one would be MYST, which you can beat in 5 minutes if you already have all the knowledge? -- @katewillaert.bsky.social, April 7

Kicking at fuzzy genre boundaries is one of my favorite things in the world, and indeed I had some thoughts there! Let me expand them into a blog post.

First up: genre boundaries aren't defined. I mean, they're not created by definitions. It's a "what I mean when I say X" game. No, worse: it's a "what this community means when they say X" game, and who's the community, anyhow? But I'll lay my own tracks; you can decide whether to follow.

I did not play Metroid or Castlevania because I didn't have Nintendo. My first console was a Playstation. Okay, PS1 had Symphony of the Night, but I didn't play that. I played Soul Reaver, which is where I encountered the gameplay model that people would later start calling "metroidvania".

I wrote (in 2001!):

You spent your time and brainpower exploring, trying to work through some remote corner of Nosgoth, and at the end of each journey was a creature that you fought. Killing the creature gave you some new ability -- climbing, swimming, and so on -- which let you enter the next chapter. -- me, recalling Soul Reaver in my review of SR2

I didn't specify "going back to an earlier area to discover new paths, using that ability." That was a vital aspect though. I loved the feeling of having to think about the game world as a whole. Gained swimming powers? Gotta remember that lake you crossed earlier! You couldn't just think about the current location, because the key to progress might not be in the current area.

So yes: this is absolutely a model drawn from adventure games. The most basic trope of adventure games is "find a thing, then go find where to use it." THE LITTLE BIRD ATTACKS THE GREEN SNAKE, AND IN AN ASTOUNDING FLURRY DRIVES THE SNAKE AWAY! The world must be open and freely explorable so you can make these connections.

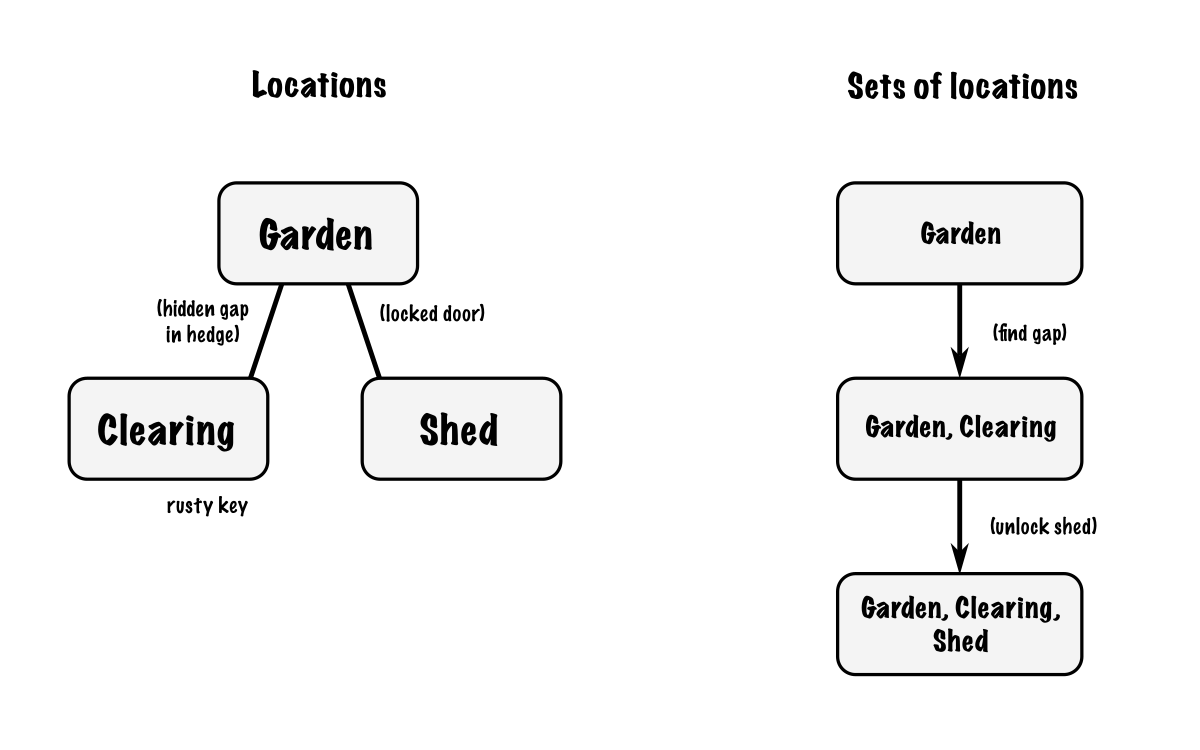

Let's extend this concept. Instead of locations and things, track the set of locations you can reach and the set of things you've found. We're no longer interested in where you are, only where you can get to. Every time you open a locked door, your set-of-locations grows larger.

See what this means? A game with no backtracking is a game where you never lose progress or get stuck. That's exactly the Loom/Myst adventure model! To revisit an "earlier state", you'd have to make a move that destroys an item or blocks access to a location. Infocom games and the early point-and-clicks were full of such situations -- but that kind of design fell out of vogue in the 90s.

...It sure sounds like the older, "cruel" adventure style is the real open-world game, while the newer "merciful" style is narrower and doesn't make you think about the whole game. Isn't that what I'm saying?

Kind of! There is a quality I miss about the old games. Not just because I was young in the old days... My pocket example is the Dispel Magic scroll in Enchanter. You could solve several puzzles with it, but it was a one-shot spell. Where to spend it? Figuring this out meant -- yep -- considering all the possible world states you could get into by using up the spell. A world where the guarded door was unlocked? A world where the tangled box was open? What other solutions would work in these worlds? A meta-open-world game!

But of course with Infocom's primitive play system, exploring these worlds meant a lot of save-file juggling. Not fun -- especially on floppy disk. But that was life in the 1980s. See this post for a deeper exploration of that era and what those "you can lose" games brought to the table.

How do we keep that sense of exploring alternatives, but avoid the frustration of juggling save files? (Or even the guilt -- you save-scummer!) Obviously, you make resetting the world a game mechanic, complete with an in-story explanation and a convenient UI for managing state. Which is how I got to Hadean Lands, of course.

And that brings us back to "metroidbrainia" land. You don't need a time loop for a metroidbrainia game; Hadean Lands isn't really a time loop. But it sure is easy to think of the metroidbrainia genre as "time loop puzzles".

Let's unpick this. We got to the metroidbrainia by taking the metroidvania idea -- "go back to an earlier area with a new tool or ability" -- and substituting "new knowledge". You don't have to defeat the swim-demon or buy a shovel or pick up a spell scroll; you just have to know what to do. You could have done it at any time, if only you'd known. That's the key.

A problem that you can solve only if you know how? We call that a "puzzle;" that's what the word means. This is what Kate Willaert is getting at above, and she's quite right.

And yet, Outer Wilds really did feel electrically new. It wasn't a retread of that Myst fireplace puzzle. (Which, to repeat the original comment, you could solve right off the bat if you knew the combination. Bypass all four puzzle Ages and go straight to Atrus.) So what was different about Outer Wilds?

It isn't the time loop. The time loop is a way to emphasize the pure-knowledge nature of the puzzles. The game wipes out all mechanical progress every loop, so you only have your accumulated understanding. And, of course, the time loop means that the game can let you get lost, get stuck, blow up your spaceship, crash into the sun (oh, so much crashing into the sun) -- no biggie, just reset. All the "unwinnability" annoyances get swept away with a single broom.

But, strictly, none of those knowledge puzzles have to do with the time loop. You could imagine doing the same kinds of puzzles in a game which had other workarounds for death and unwinnability. Tougher spaceship, tougher skin, whatever. You'd fly around and try things multiple times, instead of resetting the world on each try.

(Obviously the story of Outer Wilds is all about the time loop. That's not what I'm talking about here.)

It isn't the idea of going back to an earlier location and doing something different. That's been a popular adventure trope since, oh, Zork 1. (When you put all the treasures in the trophy case, you discover a map that shows a new path from the very first location.) "Back to the beginning" is simply good narrative closure. It doesn't give that sense of if only you'd known -- after all, Zork's map isn't an information puzzle. The hidden path is genuinely not accessible until you solve the rest of the game.

(Jason Dyer had to remind me about The Prisoner. O the embarrassment! The layout is a lot like Zork 1. You reach the finale by going back to the Caretaker -- #2, one of the first characters you encounter -- and saying a specific thing. But again, this ending move isn't available until you've gotten at least 850 points by playing other parts of the game.)

No, the division I want to draw between Myst and Outer Wilds is about the intended play experience. That's always shaky ground; people play the game in front of them, not the game the author wants them to play. But the assumption of Myst is that your play-through is a story, your personal exploration story. You begin at the beginning, explore, take notes, solve puzzles, and eventually (since there are no dead ends) reach the end. If you were writing a journal (popular!) then you might omit some of the repetitive fruitless wandering, but you'd write down every single clue, right? Same goes for the published strategy guide, which is inevitably presented as a journal. Shortcutting the puzzles is possible but the notional protagonist didn't do that! That's speedrun-fodder, and speedruns are a glitch aesthetic.

Yeah, the bad endings are a hitch in this seamless-narrative picture. But you only reach them late in the game, by which time you almost certainly have a save file. Or a bank of save files if you're an adventure-game fanatic. Almost nobody would have reached a bad ending and then started over from the beginning! And these days, Myst has autosave. So you can effectively UNDO with a couple of clicks. This very much reads as "how the game should always have been", even for us old-timers.

The other hitch is that the older '80s adventures are anything but a seamless narrative. You die constantly! You waste critical items on stupid ideas! You have to keep a bank of save files! We just discussed this.

We wanted to believe in a narrative through-line. Graham Nelson's seminal "Bill of Player's Rights" (May 1993) talks up the implicit assumption of continuous narrative:

Bill of Player's Rights [...] 3. To be able to win without experience of past lives 4. To be able to win without knowledge of future events

But Graham immediately has to hedge. In an expanded version (Jan 1995), he notes "This rule [3] is very hard to abide by." He gives three examples of puzzles that break the rule, but which still might be considered "fair" by contemporary adventurers. You just can't get through the Infocom era without a reckless attitude: try everything, see what fails horribly, restore an earlier game and try again.

Outer Wilds unquestionably calls for the same attitude; except the "restore" is a diegetic time loop. It's a game of trying wild stuff and dying. And yet, Outer Wilds feels nothing like Zork either! What am I trying to get at?

I think this: solving a puzzle in Zork or Myst feels like, well, solving a puzzle. It's right in front of you. You have a machine or a giant mirror or a row of buttons, and you mess with them. The puzzle responds. You might realize that another part of the puzzle is elsewhere (Myst loves pipes!) and then you run over there to mess with that, but it's still stuff that's right in front of you.

Solving a puzzle in Outer Wilds always happens elsewhere. Is "puzzle" even the right word? It's research; it's discovering secrets. You go out and try things and make discoveries and let them ferment in your brain. Then there's a moment of synthesis, and you shout "Holy crap! The secret was right there in front of me!" And then you go back and apply what you've learned.

...You know, that moment did exist in '80s adventures. It wasn't solving a puzzle; it was solving a puzzle in the shower. (For me that was the Elvish-runes door in Journey.) It was when you said "argh" and walked away from the game, took a walk, ate dinner... and then the lightning struck.

Every classic-adventure fan has experienced that moment -- but it's a rarity. You solve most puzzles by sitting in front of them. The metroidbrainia model ensures that every puzzle you solve feels like that thunderbolt. That's the genre keynote.

This lets us pry open another confusion: why games like Animal Well and Tunic regularly get labelled as "metroidbrainias". (Not to mention Blue Prince, the game that you don't need another review of so I'm writing this post instead.) In these games, you do go out and gather items and powers and treasures. (And put them in the trophy case.) But the game is careful to put more weight on what you do with the power than on the power itself. You may have to do a lot of platforming (Animal Well) or combat (Tunic, if you don't disable it) but the knowledge-based "brania" gameplay remains at least as important.

So there's my account. The Nature of the Metroidbrania Revealed. Does this help us create new and better games? I dunno, maybe. I'm describing a feeling rather than a strict definition. Much less a recipe -- you don't get recipes for better games; you have to do the work. But maybe it's a way to talk about that work. Let me know.

Comments from Mastodon (live)

Please wait...

This comment thread exists on Mastodon. (Why is this?) To reply, paste this URL into your Mastodon search bar: